North Carolina’s 2022 primary election is set for May 17, and almost all litigation over new state legislative and congressional district maps has come to a close. The whole process of redistricting, which began following the results of the 2020 Census, has sparked controversy and can be difficult to understand.

Dr. Andy Jackson serves as Director of the Civitas Center for Public Integrity at the John Locke Foundation, where he specializes in election policy. He joins us on this week’s Family Policy Matters radio show and podcast to clearly explain North Carolina’s redistricting process, and detail how our three new district maps could affect the 2022 election.

Due to COVID, this most recent redistricting process was extremely truncated, explains Dr. Jackson, and that is why is has been even harder to follow than usual. This year, the General Assembly didn’t get the 2020 Census data until September 2021, “so they didn’t even start drawing the maps until last October, which was about six months later than they usually do.”

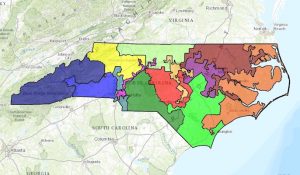

While all three original district maps drawn by the General Assembly were rejected by the North Carolina Supreme Court, the State House and State Senate maps that were subsequently redrawn by lawmakers were upheld. The Congressional map, on the other hand, was rejected again. It was drawn to be a “6-4-4 map, which means that there were 6 Republican-leaning districts, 4 Democratic-leaning districts, and 4 really, really competitive districts…” explains Dr. Jackson.

Now, the new court-drawn Congressional map in effect is a 7-6-1 map. “Depending on how you interpret that, it could be that [the trial court] thought that having that closer divide was more balanced, or it could be a way of protecting Democrats in this next election,” says Dr. Jackson.

“I think there are relatively few people that are satisfied with the process,” he continues. “The problem is how are you going to define a fair map? […] I don’t think we’re ever going to have a happy resolution where everybody’s going to agree that this is what a fair map looks like. I think we’re just going to end up having to continuously muddle through in this process.”

Tune in to Family Policy Matters this week to hear Dr. Andy Jackson go step-by-step through North Carolina’s redistricting process.

TRACI DEVETTE GRIGGS: Thanks for joining us for Family Policy Matters. Redistricting! As a result of the 2020 Census, North Carolina gained an additional seat in Congress. Population growth and changes across the state mean that lawmakers and lawyers have been furiously working to redraw district maps.

Dr. Andy Jackson is Director of the Civitas Center for Public Integrity at the John Locke Foundation, where he focuses on government compliance with the law, especially regarding election policy. Well, he joins us today to try to explain as simply as possible what’s going on and what it all means for North Carolina voters, who will head to the polls in a matter of weeks for primary elections.

Dr. Andy Jackson, welcome to Family Policy Matters.

DR. ANDY JACKSON: Thank you for having me.

TRACI DEVETTE GRIGGS: For those of us who just hear the clamoring about this redistricting, who may not really understand why it’s such a big deal, talk about the process of redistricting, and why does that matter so much to all of us?

DR. ANDY JACKSON: I’ll do the second half first there; it matters so much because it puts us in the districts where we vote. It determines who our representatives in the General Assembly will be, who our representative in Congress will be. Also, how the maps are drawn can affect the balance of power especially in the North Carolina General Assembly, so that depending on how you draw the maps, one party or other could greatly benefit, and that could affect what kind of policies affect our everyday lives.

TRACI DEVETTE GRIGGS: What is the connection between the federal census that’s done every 10 years and redistricting?

DR. ANDY JACKSON: We’re required to have—and this is from a couple of Supreme Court cases about 60 years ago—we’re required to have one person, one vote in our district’s elections. So what that means is that every district has to be roughly the same size in population, and because of that, when we do the census every 10 years, that kind of shows where our population has changed. What areas have grown, what areas have shrunk in terms of population. So, they have to redraw the district so that all those districts are about the same size in population. As a practical matter, that means over the last couple of censuses— which are done every 10 years—cities, the urban areas, especially your Wake Counties, your Mecklenburg Counties, they have grown. So, they are getting more representation in the General Assembly, whereas some of your rural areas are getting less.

TRACI DEVETTE GRIGGS: Okay. So what is the process then for redistricting in North Carolina? How do they even get started on that?

DR. ANDY JACKSON: This year of course was a little unusual because the census data came in late because of all the government restrictions surrounding COVID. But what you’re supposed to do is you get the census data—it’s collected in every year that ends in a zero, generally speaking. Then once the General Assembly receives that data from the Census Bureau where they know basically where everybody lives, then they draw the districts so that they meet that one person, one vote requirement. Usually, they draw the districts well in advance, but this year it was a very truncated process because they didn’t get the data until last September. It took them another month to process the data, so they didn’t even start drawing the maps until last October, which was about six months later than they usually do.

TRACI DEVETTE GRIGGS: Well, let’s talk first about the Congressional districts. How do these new maps affect those?

DR. ANDY JACKSON: Well, this was a really interesting case, because this is the one where they are neither the original maps drawn by the General Assembly, nor what we call “remedial maps” drawn under court order by the General Assembly. The trial court in that case decided that they weren’t going to accept the new maps written by the General Assembly under court order. Instead, the court said, “Well, we’re going to draw our own map.” So, they acquired these three individuals—they’re called special masters—and those special masters drew the map instead.

What’s interesting is what the General Assembly had submitted as a remedial map was going to be what we would call a 6-4-4 map, which means that there were 6 Republican-leaning districts, 4 Democratic-leaning districts, and 4 really, really competitive districts where they could have gone either way, depending on how people were voting that year, and that’s an unusually large amount of competitive districts for any state. Just because of where people live, it’s generally hard to draw really competitive districts. So the court rejected that and what they submitted is essentially a 7-6-1—7 Republican, 6 Democratic, and one swing district. You know, depending on how you want to interpret that, it could be that they thought that having that closer divide was more balanced, or it could be a way of protecting Democrats in this next election, because people are expecting this to be a Republican wave election coming up this year.

TRACI DEVETTE GRIGGS: So tell me about these special masters. Who are they and where do they come from?

DR. ANDY JACKSON: Special masters are appointed by courts to either draw districts or review districts. You have to remember that a judge may not be an expert or may not have enough expertise in redistricting to judge for him or herself whether or not these districts are fine. So, they bring in these people—this time there were three former judges (the one whose name I remember is Bob Orr who used to be on the North Carolina Supreme Court). There were two others. So, they were brought on specifically to ascertain whether or not these maps that the General Assembly submitted fit the criteria, fit the orders given by the North Carolina Supreme Court earlier this year.

TRACI DEVETTE GRIGGS: Okay, so let’s talk now about the General Assembly. There are two sets of maps, one for the House and one for the Senate here?

DR. ANDY JACKSON: Yes, and the House map was interesting because that was kind of the kumbaya moment when they were drawing the House map. The House map originates in the House, and it was very much a compromise between Republicans and Democrats. You could argue that Republicans gave away more than they needed to, but it ended up being, I think, only 5 Representatives out of the 120 voted against the House map. So that was a highly cooperative business there.

The Senate was totally opposite; the sides were dug in. Republicans have a majority in the Senate, so they were able to pass it, but it was a strict party-line vote. And that one is probably closer—depending on what measures you use to decide if a map is legal or not—the Senate map is probably closer than the House map, but it’s also more beneficial to Republicans than the House map is comparatively. They have a stronger advantage. So, despite that, both of those maps ended up getting approved by the court.

TRACI DEVETTE GRIGGS: So when you said that this was a kumbaya moment, is that a reflection of where we’re going? Are we going to see some more cooperation, or do you think this was just a fluke?

DR. ANDY JACKSON: I would say it’s probably just a fluke, because the House leadership maybe have decided that they wanted to not have this much contentiousness. One of the things that they did do, though—and this may have been the reasons the Republicans were okay with something that at least on the surface looks like it’s beneficial to Democrats—is a lot of the seats that are leaning towards the Democrats on this new map are still relatively competitive. The Democrats are only up an average of, say, two or three percentage points, and that means when Republicans have a good year, they could still win a majority or even a super majority. And as a practical matter, Republicans really wants a super majority, because they can’t get policies past Governor Cooper’s veto if they don’t get that.

TRACI DEVETTE GRIGGS: You’re probably in tune with how people are feeling. Are they relieved? Are they angry? What’s the sense out there?

DR. ANDY JACKSON: From what have seen as far as reactions go, I think obviously Republicans are upset because they lost the maps that they wanted to have, that they had originally passed. Some Democrats are happy. Others are thinking that this is better than what they had originally, but it still isn’t really what they would call a “fair map.” Once again, people have different definitions of what a fair map is, but it’s certainly not as advantageous to Democrats as some of them would’ve liked. I would say, I think maybe they’re ready to get this behind them and they’re kind of relieved in that sense, but I think there’s relatively few people that are satisfied with the process.

TRACI DEVETTE GRIGGS: Is there a way to stand back and just judge whether or not it’s ever possible to have a fair map concerning this?

DR. ANDY JACKSON: The short answer I would say is no, because the problem is how are you going to define a fair map? Is it a map that accurately reflects the statewide vote distribution? Is it a map that accurately reflects where people live and how people vote? Because if you look at those two different criteria, you get two very different answers. North Carolina…we’re not a 50/50 state. We’re basically a 51/49 on average state: 51 percent Republican. And so if you are a Democrat, you would say, “Well, what we should have is seats that reflect that, that the average election will also be 51/49.” The problem is, with our political geography, Democrats tend to be more concentrated in cities where Republicans are more spread out. So, in order to achieve that, you actually have to draw districts to benefit Democrats; you basically have to gerrymander if you’re going to prevent gerrymandering in that name. So, I don’t think we’re ever going to have a happy resolution where everybody’s going to agree that this is what a fair map looks like. I think we’re just going to end up having to continuously muddle through in this process. And we may come to a day where we kind of know where the right lines are, and so the General Assembly won’t be successfully sued again, but I’m not sure we’ve arrived at that yet.

TRACI DEVETTE GRIGGS: Looking at what has happened over this long process, what is your feeling of judges and courts? We’ve had a sense, at least in the past, that judges were supposed to be impartial. Do you feel better about that or worse about that, having seen what happened throughout this whole redistricting process?

DR. ANDY JACKSON: Well, I think I’ll answer that with a projection right now. We have two North Carolina Supreme Court seats—both of them are held by Democrats—both of those seats are going to be up this year. One of those, the incumbent, Sam Irving IV, is running for reelection. The other one’s going to be an open seat. If Republicans win both those seats, and we revisit this issue in two years, I have a feeling that we’re going to get a very different result. So, I think that tells us all that we need to know about this, that even in the court system, it’s still quite political. I think that it’s no accident that it was the four Democrats that voted for overturning the maps and that the three Republicans voted against. So we certainly, at least on the terms that were done in this case, we certainly don’t have any kind of concurrence about what is a fair map and what fits in North Carolina’s constitution with regards to map drawing.

TRACI DEVETTE GRIGGS: So our judges are more and more important for us to consider and vote for, aren’t they, these days?

DR. ANDY JACKSON: Oh, indeed.

TRACI DEVETTE GRIGGS: So what about long term lessons? Do we come away from this process with anything that we can take into the next time?

DR. ANDY JACKSON: I’d like to think every time—and this happens with some regularity in North Carolina—every time a court overturns a map that it’s kind of a learning process, that the General Assembly learns, “Okay, we can’t do this.” The most famous one is the Stephenson v. Bartlett case, which was 2002-ish. And in that one, they ruled that they had to try to keep counties whole as much as possible, because I don’t know if you’ve seen some of the older maps that we’ve had in North Carolina, but they had these real squiggly lines that would cut across parts of several counties to unite other areas. I mean, that was classic gerrymandering. And then Stevenson ruling was that, “Well, you can’t do that. As much as possible, you have to keep counties together.” And then we had another case a couple years later, I think about 2017-ish, with regard to using racial data, so now we don’t use racial data when we’re redistricting.

And so there are parts of this last case that probably are going to get overturned, but I think that for example—and I won’t get too wonky this—but there are these mathematic models that show you the probabilities of the distribution of seats in a state. And I think that the General Assembly’s going to probably have to keep that in mind when they’re drawing districts in the future. I think that will help with regard to future court cases, no matter how the Supreme Court goes.

TRACI DEVETTE GRIGGS: Dr. Jackson, where can our listeners go to follow developments related to this, and to follow your work?

DR. ANDY JACKSON: Well, I’m over at the John Locke Foundation, which is johnlocke.org. And I write there regularly, my colleague Jim Sterling writes on election issues regularly, and we have a lot of interesting stuff over on our page.

TRACI DEVETTE GRIGGS: Okay. Dr. Andy Jackson, Director of the Civitas Center for Public Integrity at the John Locke Foundation, thanks so much for being with us today on Family Policy Matters.

– END –